In 2013, I spent a few months living in Orlando, Florida. I worked for a small transportation planning and engineering firm. While most of our work focused on improving traffic corridors in Central Florida, I would regularly drive to Miami for projects. It is a four-hour journey where you see Florida’s stunning landscape, from the expansive Everglades to small coastal communities. Since leaving Florida, I haven’t spent much time thinking about those long drives until this past week.

Delray Beach after a King Tide in 2016 (Photo Credit: Larry Richardson)

Earlier this last week, I was asked by the City of Delray Beach to help them address a growing concern: sea level rise. Delray Beach, a coastal community of 60,000 just 55 miles north of Miami, has seen increased flooding as a result of climate change. After several years of relentless storm surges and flooding, the City is currently working on rehabilitating its seawalls for residents who live along the intracoastal waterway. Despite this rehabilitation work, the City received a report in early February estimating that future seawall and stormwater infrastructure will cost $378 million over the next 30 years. This is a huge undertaking for any city and especially a city of 60,000 people. To put this in perspective, the City of Delray Beach’s Capital Improvement Plan (the next five years of infrastructure needs) budget is nearly $80 million for the fiscal year of 2018-2019, and current seawall renovations amount to only 4% of the total amount. But, this problem isn’t unique to Delray Beach.

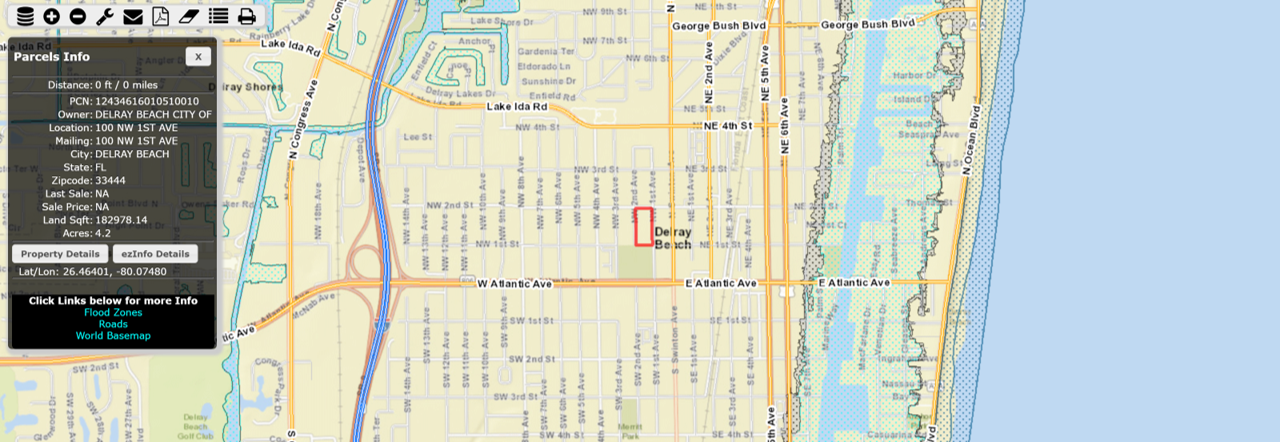

FEMA Flood Mapping of Delray Beach

NOAA and FEMA show that an expected two-foot sea level rise (which is a conservative estimate by many standards) by 2100 will impact many of Florida’s coastal towns, especially Miami and the Keyes. Without considering state-wide political hesitation to combat climate change (which is addressed in Jeff Goodell’s The Water Will Come), these coastal towns only have so many tools at their disposal to protect their communities from rising sea levels. Raising taxes to pay for seawall and stormwater infrastructure is not only politically unsavory, it is restricted by the Florida’s tax code. As you might know, Florida has no state or local income taxes. This means, that the bulk of state and local revenues come from property taxes. This might be why I saw so many luxury condominiums on my frequent drives up and down the coast. For the most part, the taxes on these properties are used to pay for everything, from public education to sanitation networks. Even though coastal cities could work together to lobby the state for additional funds or policy changes, they are often not incentivized to do so. This means that the outdated and overstressed National Flood Insurance Program, that many property owners pay as protection against flood damage, becomes a crutch for adequately addressing sea level rise.

So, in putting together a list of financial strategies for the City of Delray Beach, I had to consider all these constraints. And, it seemed that others had done the same. A group of lawyers outlined a list of strategies for Florida cities in an article from 2017. And, the city of San Francisco did the same, considering the larger state and federal policy constraints. With this information, I decided to do a preliminary analysis of the possible financial strategies for seawall and stormwater infrastructure. That’s what you find here; an eager attempt to understand the landscape of public financing for seawalls and stormwater infrastructure.

Click Heat Map (or here) to see more details

To understand and compare these strategies requires a more in-depth assessment. The heat map begins to outline these considerations and rank the strategies. And, the City of Delray Beach will need to use a mix of these strategies to be able to meet infrastructure needs. And, some of these strategies require the city to rethink what adaptation means.

When planning for 30 years of infrastructure, we must consider irreversible environmental trends. This heat map also includes strategies for financing adaptive coastline and managed retreat plans. While seawalls can save communities from current and imminent flood conditions, they have negative consequences for ecosystems and neighboring communities. Adaptive coastline and managed retreat plans would relocate coastal residents to inland areas, with a focus on shoreline restoration, creative reuse, and conservation. With this approach, the city could leverage additional grants and funding tools. This plan would be an investment in the safety of its current and future residents. It would require a longer and more involved community engagement process where residents would be encouraged to reimagine their lives and the future of the city for their children. While past relocation efforts have been less than successful, renewing “debates over local autonomy, eminent domain, and forced removal”, there are hopes that a phased, transparent, and collaborative process could result in more sustainable outcomes for coastal communities.

Climate change is affecting how we live. Are coastal cities ready to make hard choices to protect ther communities? And, if they can’t, will communities be ready for what’s to come?